With global dry powder at a record $1.5 trillion, is the Covid crisis simply an opportunity for private equity firms to snap up firms on the cheap, or will the decade-long rise of private equity in Europe finally start to slow? By Mark Latham.

The coronavirus pandemic brought an end to one of the longest bull markets in modern history during which mergers and acquisitions reached record levels.

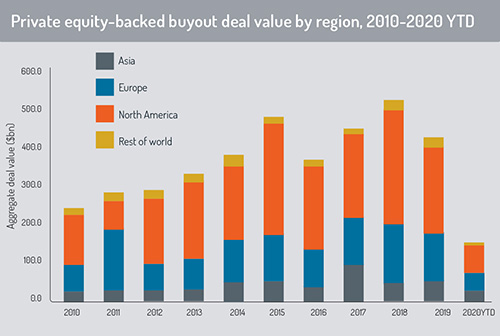

Global deal-making slowed to a ten-year low during the second quarter of 2020 and in Europe, the first half of the year was the worst six-month period for private equity deals since the global financial crisis of 2008/09.

According to data from Imperial College London’s Centre for Management Buy-Out Research (CMBOR), there were 205 private equity transactions in Europe in the first half of 2020, down 38% compared with the first half of 2019. That’s also lower than the previous record low (207 transactions) in the first half of 2009.

However, the total combined value of deals in Europe fell by just 7% year-on-year to €41.1 billion in the first half of this year, held up by a small number of large investments.

This included Europe’s biggest buyout deal in a decade: the €17.2 billion acquisition of Thyssenkrupp’s elevator business by a consortium led by Advent International and Cinven.

This included Europe’s biggest buyout deal in a decade: the €17.2 billion acquisition of Thyssenkrupp’s elevator business by a consortium led by Advent International and Cinven.

Meanwhile, as the pandemic spread, the European arm of the $207 billion (€184 billion) US private equity group KKR took a majority stake in cosmetics group Coty in a cut-price valuation.

But the bullish view held by some of the largest private equity firms is not shared among smaller and increasingly more cautious players.

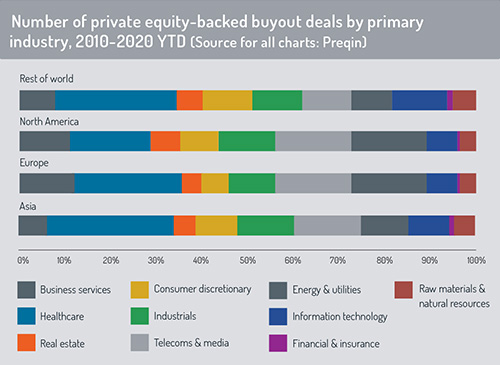

CMBOR’s research found that, in the first half of this year, the technology, media and telecom sector garnered the most interest, with 55 European deals, collectively valued at €15.3 billion, completing.

There is, though, evidence that many investors view the outlook for private equity as fairly bright. A survey from the advisory company Willis Towers Watson, published in July, showed that private equity investments are weathering the impact of Covid-19 across multiple sectors and geographies.

The research concluded that private equity-owned companies have structural advantages that enable them to cope with crises better than non-private equity-owned firms.

The survey of 36 private equity funds, representing more than 300 portfolio companies, also found that despite a subdued environment for exit deals in the first six months of the year, there has been little evidence of forced exits.

It also showed that the significant turmoil in capital markets has had little impact on the capital structures of portfolio companies, with 87% of respondents indicating that their holdings were unlikely to breach covenants as a result.

Only 13% said holdings were either close to, or likely to, breach covenants over the next two to three months.

Andrew Brown, head of private equity research at Willis Towers Watson, says: “In addition to the expertise provided to them by private equity managers, the additional access to equity and debt capital from their sponsors may have provided some respite.

“Beyond the short-term dislocation, we also see a number of opportunities where we can continue to deploy capital, notably in technology, healthcare and consumer staples. With deal volumes depressed, there appears to be far less competition for opportunities and as a result, potentially better entry pricing.”

Murky valuations

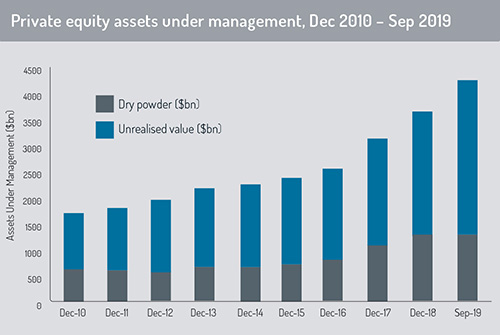

Figures from data provider Preqin show that assets under management (AuM) in private equity globally stood at a record high of $4.5 trillion (€4 trillion) at the end of 2019, of which Europe-focused AuM was $807.3 billion (up 10% from December 2018).

Dry powder – committed but not yet called up capital – also stands at a record high, with Preqin estimating a global figure in July of $1.5 trillion and Europe-focused dry powder at $255.1 billion.

Christopher Beales, senior manager for alternative asset content at Preqin, said that while first-quarter activity in the private equity sector was down, it was not apparent until the spring that a big slowdown was underway.

Christopher Beales, senior manager for alternative asset content at Preqin, said that while first-quarter activity in the private equity sector was down, it was not apparent until the spring that a big slowdown was underway.

“Because of the length of time private equity deals take to complete and because there was a fairly robust pipeline, deals got over the line throughout January, February and even March,” he says.

By April, however, the impact of social distancing meant that the cancelled meetings needed to get deals “over the line” had led to the “pipeline drying up”.

“Worsening company cashflow and growing uncertainty over forecasting mean that valuations are more murky than they were at the start of the year,” he adds.

“Overall the number of deals is dropping, but there are occasional pockets of deals being completed for larger amounts which are propping up the general picture.”

Telecoms is a sector that will likely thrive as a result of the pandemic, says Beales, as more employees working from home and remote locations will require infrastructure investment in suburban areas. Healthcare is also likely to see renewed investor interest because of the pandemic.

“The number of real estate deals has fallen throughout the crisis, but with retail increasingly shifting to e-commerce, investment in industrial warehousing and logistics is likely to increase,” he says.

“At the moment, everyone is waiting to see how consumer behaviour is going to change. Deal activity will bounce back at some point, but everyone is uncertain about when is the right time to re-enter.”

Pawel Gierynski, managing partner at Warsaw-based Abris Capital Partners, denies that the crisis is simply an opportunity for private equity firms to snap up bargain companies.

One of the largest private equity firms in central and eastern Europe, Abris’s last fund raised more than €500 million and its total AuM is €1.3 billion.

“No doubt there will be some opportunities to buy businesses cheaper but to be honest, it is not something we will be really focusing on,” says Gierynski.

The pandemic differs from the global financial crisis, he says, when firms were struggling with liquidity and “it was just a matter of restructuring their balance sheets, providing some more equity, repaying debt and off you go with a very good company.

“Now, it is not really liquidity that is the main issue for most firms. Some firms are struggling with supply chains, some because they have weak management. This crisis is going to be a very strong test of management capabilities.

“What we are trying to focus on is companies that are performing very well in this crisis, which are potentially more expensive now. The important thing is that they have proven themselves through these challenging times in terms of daily resilience and management capabilities.”

Deal-making in central and eastern Europe is down but has not entirely dried up, says Gierynski, whose company has completed two “bolt-on” acquisitions since March.

Deal-making in central and eastern Europe is down but has not entirely dried up, says Gierynski, whose company has completed two “bolt-on” acquisitions since March.

“However, other acquisitions have been put on hold because we were not sure how the businesses will cope with the crisis and we want to get better visibility. We will review those maybe towards the end of the year, but not now.”

Black swan event

Karsten Langer, managing partner for Europe of the $10 billion US-based private equity company Riverside, says that while buyout opportunities will arise through lower prices, any decision has to be balanced against the fact that many firms will now present more risk than before the pandemic.

“This is a true black swan event, and its impact is going to be very different on different parts of the economy,” he says. “Some sectors – like restaurants, hospitality and hotels, tourism and entertainment – have been very badly affected and many firms have dropped in value.

“The question, as an investor, is whether you are willing to buy today in the belief that the firms will come back to what they were next year or the year after that. The risk in making an investment is trying to predict what the future is going to be for an industry and it is too simplistic to say that because things are cheap now, we should buy up cheap companies; the market is much more sophisticated than that.”

Riverside, a growth buyout specialist which mostly invests in the lower end of the middle market, has recently cancelled a couple of potential asset sales as “we decided that now was no longer the best time to sell and, globally, any private equity group would say the same thing”.

Langer adds: “What often happens when you have a crisis like this with a market correction is that buyers are very quick to want to pay less, but sellers are not quick to want to accept less, so the bid ask spread widens and the chance of buyers and sellers meeting each other becomes smaller.”

Given the trend towards more highly leveraged and “covenant-light” private equity deals in recent years, some fear that private equity-owned firms will become increasingly vulnerable as the global economic outlooks worsens.

Whether the future is bright for the sector will largely depend on whether the opportunities to spend record piles of dry powder outweigh the losses on many of the hard-hit firms in existing portfolios.

© 2020 funds europe