A pan-European fund supermarket should be easier to set up than eBay’s global shopping centre. But platforms still lack the depth of coverage, finds Fiona Rintoul.

The funds industry is lagging behind the rest of the world of commerce when it comes to delivering an online marketplace with a broad geographical reach. This is remarkable given the drive towards open architecture and regulatory harmonisation, which in Europe should facilitate such a development.

In other areas of commerce online marketplaces are flourishing. Sitting in the UK, one can, on eBay, buy literary magazines dating from the Soviet era from individuals in Leipzig, Dresden and Erfurt, or buy books that are unavailable in Europe but obtainable from small publishers in the US via Amazon.

One might think, then, that an online marketplace for funds would have developed, but a glance at what’s available online in Europe today tells us that no such thing exists. There are online fund platforms, of course, in both the business-to-consumer and business-to-business spaces. But for the most part they are national rather than European entities. And in many cases, these platforms are but an extension of the status quo; they are run by the big banks that already control distribution and they are driven by those banks’ proprietary products.

“Many of the dominant platforms in France, Spain and Italy have evolved from the inhouse asset management division of a major bank,” notes the new UK Fund Platform Report from Lipper Feri. “Two such groups, BNP Paribas and Santander have developed the FundQuest and Allfunds Bank platforms respectively. Although both platforms are actively trying to increase non-group assets, all-important volume has been built by the significant inflows into group multi-manager products.”

In other words, most platform users are not getting anything new. They are not getting the fund equivalent of magazines from Erfurt or books from small and obscure American presses.

Beyond local markets

Fund supermarkets first appeared in Europe back around the turn of the millennium. It wasn’t a great time to start. A market crash quickly ensued. Everyone struggled – but the new platforms struggled more than most.

“A lot of local fund supermarket players had a rough time after 2000,” says Zin Bekkali, head of business development and processes at Fortis Investments. “They didn’t succeed in quickly covering their set-up costs.”

The supermarkets survived, however, and recent news has been more positive. In the UK, which some argue is more suitable for supermarket platforms than mainland European countries because of the high percentage of funds sold through individual financial advisers (IFAs), high-profile platforms such as Cofunds and Fidelity’s FundsNetwork have started to gain market share.

Cofunds, for example, which is owned by a consortium of financial services firms comprising Legal & General, IFDS, Newhouse Capital Partners, Threadneedle, Jupiter and Prudential, now claims to be the fifth largest administrator of UK stocks-and-shares ISA (individual savings account) business and the seventh largest onshore bond provider in the UK. It puts its assets under administration at 30 June 2007 at £13.4bn (e20bn), up 45% on the previous year.

These kind of figures indicate, if not rip-roaring success, at least viability. “In the UK, it took a long time for fund supermarkets to become profitable,” says Alec Hoffman, head of transfer agency at the consultancy Etheois. “They are only just arriving at a profitable situation now.”

Meanwhile, in the business-to-business space the undisputed leader among fund platforms is Allfunds. The Spanish-Italian joint venture, which is co-owned by Grupo Santander and Sanpaolo IMI, has €42bn under administration and distributes 8,000 funds from 150 asset management companies to some 140 financial institutions in Europe and Latin America.

Allfunds says it is “the largest third-party mutual fund platform in Europe”. It is also the platform with the greatest claim to be pan-European. In Europe, Allfunds is currently present in Spain, Italy, Portugal and the UK, its activities in the latter being supported by its ownership of Abbey.

Other platforms have a cross-border presence, but none has achieved the scale of Allfunds. An example is Cortal Consors, the product of a 2002 Franco-German merger, now owned 100% by BNP Paribas. Despite its multinational heritage, the group has failed to achieve substantial volumes. Its AUM today is e13.7bn, down from e18.6bn in 2004, and only a part of that is funds, as the platform also offers share trading and other services.

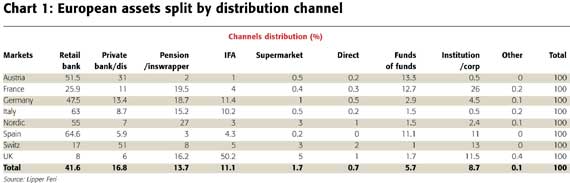

In fact, scale is an issue across the board. Chart 1 shows how low penetration is by supermarkets in most European countries. And this is a business where scale is important. Fund supermarkets’ raison d’être is their ability to offer choice at a low price. Fund supermarket sponsors therefore have to drive substantial volumes through their platforms to have any hope of making money.

The exacting economics of online platforms is one factor that has inhibited the development of pan-European platforms. “Until now platforms have been too small to think about expansion beyond

their local markets,” says Bekkali. “But now they are getting big enough. We are at the tipping point where these players will have positive cashflows.”

True pan-European platform

A true pan-European platform would, of course, be hugely beneficial to fund managers operating a cross-border business in Europe. At the moment, with the quasi-exception of a few private banks, there is no one that can offer fund managers distribution across the board in Europe.

“Even the biggest banks in Europe did not succeed in building dominant positions in more than two countries,” says Bekkali. “Deutsche Bank is strong in Germany, but it has almost no distribution presence in other key European markets such as France. Distribution is still controlled by the biggest local names.”

You might think, then, that anyone who could create a pan-European distribution platform would be able to clean up. Hoffman laughs at the suggestion. Anyone attempting to set up a pan-European supermarket would be making “a long-term investment for the future” and would face four key obstacles.

First up is the legal framework. “Ucits 3 has been helpful in the distribution of funds,” says Hoffman, “but implementation hasn’t been perfect. Some member states could be accused of protectionism. The regulation of distribution must improve, then platforms will come after.”

Other issues are the operational processing of funds, which is not yet standard across markets or paper-free, and systems. “The required complexity in systems would be high,” says Hoffman. “We are just starting to see transfer agency systems that can handle requirements in different markets.”

The other issue identified by Hoffman is “the individual tradition in distribution networks and methods in each local market”.

The UK, which is the European market where fund supermarkets have flourished best, has a tradition of selling funds through intermediaries. Mainland European markets are more bank-dominated and investors may therefore feel less comfortable buying through a fund supermarket.

Some suggest that mainland European banks also do not wish their clients to be picking and choosing from among hundreds of fund providers on a fund supermarket and therefore have not encouraged the development of platforms.

National differences

“The distribution model in mainland Europe is dominated by bank-assurers,” says Steve Cook, a business adviser at the consultancy Morse. “While there is open architecture, they are not offering shelf space. The principal way that open architecture is coming into the mainland European space is through funds of funds or unit-linked products. The fund supermarket is not the architecture that bank-assurers have chosen.”

But even if everyone were wildly enthusiastic about fund supermarkets, there would still be impediments to the creation of a pan-European outlet. The well-known mantra that there’s a European passport but a visa for each country is still required can extend beyond issues such as language and regulation.

“You can take it down to the product range level,” says Andrew Marks, a vice president with responsibility for distribution at T. Rowe Price. “There’s a huge difference in buying habits in the different European countries.”

Different countries may also require a different provider range. “When Allfunds came into the UK, they had to go out to the market again to get new managers onto the platform,” says Marks. “There was much more interest in boutiques in the UK. They had to target those groups.”

Each market also has its own tax-efficient products that investors expect to see on a platform. At the moment, the French version of Cortal-Consors is advertising the Livret A, a fixed-rate tax-efficient savings scheme. In the UK, every platform worth its salt will offer ISAs. In fact, CoFunds says its has administered 24% of total intermediary ISA sales in 2005 to 2006.

There is no help for these kind of national differences – and they are not going to go away. This is what makes Europe different from the US. The fund supermarket landscape is simply a reflection of the market as a whole. It is heterogeneous, fragmented and inefficient, and while it could (and should) become more efficient, it is never going to become a bland whole where people want and expect the same things.

Even within the much more simple business of buying and selling books or other items on online platforms such as eBay or Amazon, there isn’t really complete connectivity. When buying an East German magazine from Erfurt, for example, it can work out cheaper if you live in the UK to send euros to the seller in a good old-fashioned envelope because the cost of transferring money from a UK bank account to a German bank account could be prohibitively high.

“Today even that sector is not mature yet,” says Bekkali. “It was not easy for eBay to put one European platform in place. It had to buy some local entities to get itself working. It will be even more complicated in financial services.”

Business as usual

An eBay for funds is some way off, though by no means an impossibility. Like eBay itself if may be achieved through acquisitions.

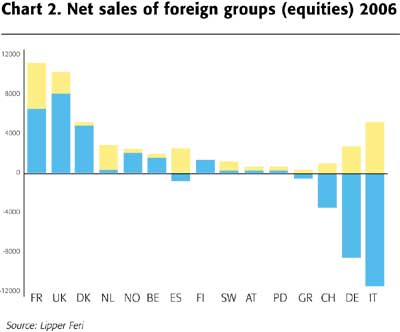

In the meantime, fund managers are doing business anyway. Figures show that cross-border funds’ share of the European market is increasing (see Chart 2). The European market may be difficult, but it is not impossible, and as long as that remains the case, fund managers will try and build a business there.

Indeed, many are now targeting other markets that are more complex still. “A lot of fund managers are turning their attention to Asia-Pacific where it’s even harder and there’s no equivalent of the European Union,” says Cook.

© fe October 2007