The Nordic funds industry claims that by working alongside regulators it has dealt head on with the controversy over alleged closet-tracking. Mark Latham reports.

While one of the biggest challenges for the global funds industry over the past decade has been the massive outflows from actively managed funds to cheaper index-tracking funds, active fund managers in the Nordics region claim that the impact of the trend on the region’s institutional and wholesale market has been more limited and that active funds continue to prosper.

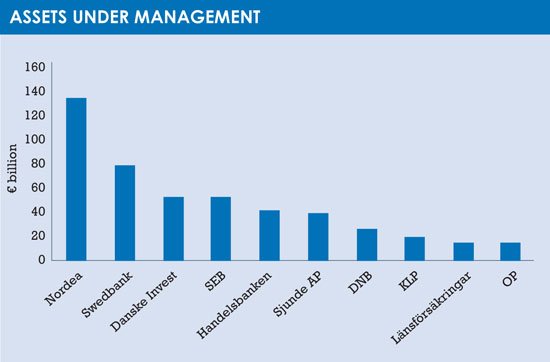

So far, at least, those claims appear to be borne out by the stats. The region’s largest funds company, Stockholm-based Nordea, enjoyed record-breaking inflows in 2016 of €14.4 billion and was, behind the world’s largest investment firm BlackRock, the second-fastest growing asset manager in Europe.

Meanwhile, Nordea Asset Management’s Stable Return Fund, which invests in bonds and equities across emerging and development markets, was the bestselling mutual fund in Europe last year, pulling in net inflows of €10.5 billion before the fund was closed to new investors in October.

And, while the talk in other parts of the industry is of consolidation, cost-cutting and jobs losses, Nordea is going in the other way, with plans to recruit up to 100 new employees, an increase of 15% on its current workforce.

But Nordea, along with other asset management firms in the region, has also had its problems. In 2015, Norway’s financial regulator rapped its knuckles for selling an actively managed fund that closely followed its benchmark in a practice known as ‘closet-tracking’.

Other asset management firms in the region that have been investigated for benchmark-hugging, as the practice is also known, include Sweden’s Swedbank Robur and Norway’s DNB Asset Management.

Other asset management firms in the region that have been investigated for benchmark-hugging, as the practice is also known, include Sweden’s Swedbank Robur and Norway’s DNB Asset Management.

Probes by regional regulators into closet-tracking at Scandinavian financial institutions followed complaints from investor rights groups in the region that consumers had been mis-sold investment products described as actively managed funds.

The allegations were that high management fees had been charged for funds that were simply tracking an index in the same way as low-cost passively managed funds.

Henrika Vikman, chief executive of Nordea Funds, maintains that the allegation of closet-tracking was confined to one of the firm’s Norwegian funds.

She also points out that, because of the concentrated nature of the local stock market, which is dominated by a small number of large firms, it is hard to attain a high active share of portfolio divergence.

Vikman adds that it is simplistic to measure the performance of an actively managed fund with regard only to its active share and that other factors are also in play.

“In order to assess the activity of a fund, you should also take into account other indicators of activity and risk, which is best done through a holistic performance review of both relative and absolute terms,”

she says.

The fact that 2016 was a “really good” year for investors was, she says, because of a greater appetite for risk-taking as investment managers rebalanced portfolio holdings of fixed income assets towards equities within balanced funds. “All Nordic equity markets performed well last year in local currencies,” she says. “Overall, the Nordic region offers an investor good diversification in terms of currency risks and markets.”

Vikman says that Nordea’s commitment to environmental, social and governance (ESG) standards – which are strongly supported by other asset managers in the region – is another reason for the company’s strong performance.

Examples of Nordea’s uncompromising stance on ESG standards include a ban, introduced in the wake of the Volkswagen diesel emissions scandal, on buying VW stocks and bonds and another ban on investing in the controversial Dakota access pipeline.

“ESG is a trend that we have seen growing, starting with the institutional market and moving towards the retail sector,” Vikman says. “Investors are demanding more and more sustainable investment.”

Looking forward, Vikman says she would like to see progress on the EU’s Capital Markets Union project, which aims to reduce Europe’s reliance on bank funding and removing obstacles for investors in Europe’s capital markets.

“There has been a lot of talk on the project but not that much agreed by the European Commission,” she says.

“We think it would be beneficial as it would introduce a level playing field for the movement of capital around Europe and the ability to sell financial products in other European countries.

“We would like this to go forward as we see it as a way to strengthen the European economy and an opportunity to take down as many obstacles to growth as possible.”

UNDERMINING UCITS

An investigation into closet-tracking by the Swedish financial regulator concluded last year that the difference between an actively managed fund and an index fund is around 1 percentage point. “While this difference might seem negligible, the difference will be substantial in the long term,” the regulator’s report concluded.

Fredrik Nordström, chief executive of the Swedish Investment Fund Association, believes that that the issues over closet-tracking in Sweden have largely been resolved, although he admits that there is still “room for improving the description of fund management strategies”.

“The supervisory authorities are on the case and have concluded that funds are on trend with lower fees and more active management in terms of active share and tracking error,” he says.

But, Nordström admits, Sweden has a major consumer-related problem following a controversy about funds invested in the country’s premium pension system.

But, Nordström admits, Sweden has a major consumer-related problem following a controversy about funds invested in the country’s premium pension system.

The scandal last year led Swedish prime minster Stefan Löfven to call for the closing of the scheme to Ucits funds and to make it an entirely state-run system.

“A legal battle between the pension authority and a small number of funds that are alleged not to put investors’ interests first has been undermining confidence in the Ucits brand in Sweden,” Nordström says.

“This has repercussions for the funds industry throughout Europe where consumers ought to be entitled to the same levels of consumer protection.”

When the Nordic countries are looked at from the outside, they might at first sight appear similar – but there are strikingly divergent investment cultures between Sweden, Norway, Finland and Denmark.

Sweden, by far the largest of the four countries and with a fund industry three to four times the size of Norway or Finland, is the country with the longest and best-established tradition of saving into financial product investments by households.

Another difference that Nordström points to is the fact that the appetite for high-risk equity funds in emerging markets among Swedish investors is high compared with other parts of Europe and Scandinavia.

This is partly, Nordström believes, because Sweden’s strong social security safety net means there is “more capacity for higher risk in household balance sheets.”

While the investment industry in the Nordics region is often thought of as being dominated by large banks, pensions and insurance groups selling products directly, there are significant differences between the Nordic countries in the way that funds are sold to investors.

Alexandra Morris, chief investment officer of Stavanger-based funds firm Skagen, contrasts Sweden’s platform-dominated market (where the move to platform-selling was pushed forward by the government’s introduction of individual savings accounts) with Norway’s reliance on direct sales.

However, the Norwegian market is steadily moving towards the greater use of platform sales and, from July this year, consumers in Norway will be able to move shares and mutual funds into individual savings accounts tax-free.

Morris expects the change will be “a game-changer” that will further boost consumer savings in Norway and see more cash going into mutual funds in the country.

“We may see changes in the ways that funds are bought and sold as competition grows and we are ready for that,” she says.

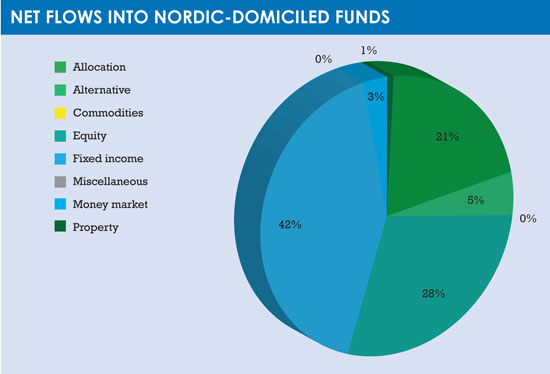

Matias Möttölä, a Helsinki-based analyst at investment research firm Morningstar, says that anecdotal evidence suggests passive funds have been steadily taking more market share in the Nordics, particularly from open-ended active funds – although a lack of data about the nationalities of investors into ETFs makes it hard to verify the flows.

“Data from brokers seems to indicate that there is strong demand from retail and institutional investors in Scandinavia for ETFs,” Möttölä says. He adds that institutional and retail investors in Scandinavia are thought to be putting substantial amounts of money into index-tracking passive ETFs domiciled elsewhere in Europe, particularly in Ireland and Luxembourg (where, for example, Nordea’s ETFs are based) – from where it is easier to sell internationally across platforms.

Despite the global swing towards passive funds in recent years, only 9.2% (€51.1 billion as of February 28, 2017) of Nordic open-ended funds are passively managed, and passive investing remains less entrenched than in the UK and the Netherlands.

“ETFs mostly have such low expense ratios that a provider must have a fair amount of assets in order to be profitable,” Möttölä says.

“From the Nordics it is hard to compete with ETFs domiciled elsewhere which are already established in the ETF space, as the competition is truly international.”

Criticism by the region’s financial regulators of firms accused of closet-indexing is “keeping asset managers on their toes”, while recent studies have shown that management fees in Nordics are moderate compared with many other parts of Europe.

“This shows that there is some degree of competition, but fees could certainly be lower in a truly competitive landscape,” he says.

©2017 funds europe