Brussels is expected to postpone implementation of the Central Securities Depository Regulation. But the delay will be short and concerns about the detail remain. Bob Currie reports.

Securities lending agents and other relevant parties are expecting the European markets regulator to postpone a far-reaching new regulation that affects securities lending – but only for four months, and the depth of concern about some of the rules is substantial.

The European Securities and Markets Authority (Esma) has advised a postponement of the Central Securities Depository Regulation (CSDR), which in large part aims to reduce settlement failures and improve efficiencies in securities markets.

The delay needs approval but it is assumed to be a done deal and the market has cautiously built the hiatus into its plans.

The CSDR includes what is called the ‘settlement discipline regime’ (SDR). Under the SDR, if either counterparty fails to meet its delivery obligations (i.e. the seller fails to deliver the required securities, the buyer fails to deliver the corresponding payment – or, in a securities finance transaction, the borrower fails to return securities when required), they will be subject to a cash penalty that is charged daily, based on the value of the transaction.

If the securities are not delivered within a required timeframe, there will be a mandatory system to ‘buy in’ these securities from another source.

Letter to the regulator

The steps to reduce settlement risk and to improve operational efficiency have been welcomed by many, but questions persist around the timing of SDR implementation and the way that elements of the regulation – such as the buy-in rules – have been constructed.

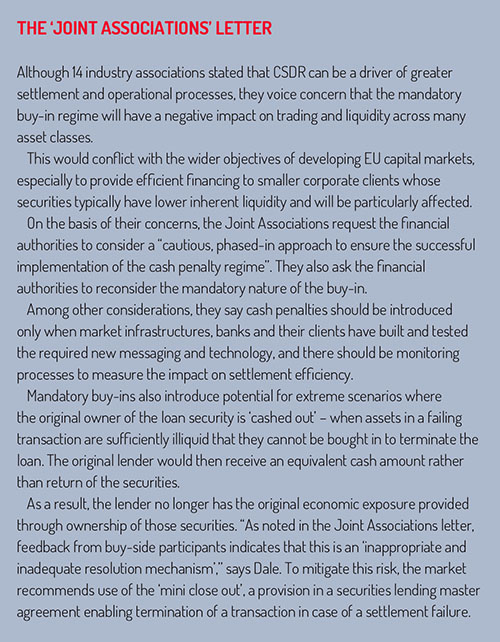

In January, 14 industry trade associations – including the International Securities Lending Association (Isla), the International Capital Market Association (ICMA), the UK’s Investment Association and the Association for Financial Markets in Europe – sent a joint letter to Esma and the European Commission recommending a delay to the penalty regime and the need to rethink some of its provisions (see box below).

The Joint Associations are positive about some elements of the SDR, indicating that improved allocation and confirmation processes, and the introduction of cash penalties to encourage timely settlement, are important for improved settlement rates.

However, “the consensus view amongst buy- and sell-side market practitioners”, they believe, is that the mandatory buy-in regime will have negative implications from a trading and liquidity perspective across many asset classes.

Potentially, this may remove incentives to lend securities in securities lending and repo markets and it may lead to wider bid-offer spreads in the cash markets. More broadly, it may encourage market participants to move settlement of less liquid securities into non-EU central securities depositories (CSDs) that are not subject to CSDR.

When the ICMA, one of the signatories to the letter, conducted an impact assessment across its membership, 100% of sell-side firms and 80% of buy-side respondents said that the introduction of mandatory buy-ins would have a negative effect on overall market efficiency and liquidity. Respondents predict that traditional lenders in securities lending markets are likely to “hold more buffers, or even withdraw inventory”, which would limit loan availability to cover short positions.

More broadly, market makers are expected to “widen bid-ask spreads by at least 100%”, with greater impact expected for some illiquid asset classes and “a full withdrawal from market making likely in some instances”.

Esma has recommended a postponement, although not in direct response to these concerns.

Acceptable costs

Esma’s recommendation to postpone this CSDR component is linked more to concerns over the readiness of the market infrastructure to accommodate SDR changes – for example, in the need for testing of the new penalty mechanism within the

TARGET2-Securities (T2S) environment, the centralised securities settlement platform operated by the European Central Bank.

The introduction of new ISO messages by the Swift messaging network due in November is also a factor because the T2S system cannot process new buy-in functionality until the messages are market tested.

But is the delay justified? Mick Chadwick, director, global head of securities finance at Aviva Investors, says that with the introduction of settlement fines under CSDR, the industry faces a significant systems cost to administer those fines. But, he says: “This is a cost that the industry can live with.”

Financial regulators can point to a number of examples where settlement fines have been introduced and this has had positive effects in terms of cleaning up settlement efficiency. For example, the introduction of a 3% settlement fine had a positive impact on combating rising settlement fail rates in the US Treasury cash and repo markets.

“The industry is sanguine about the introduction of settlement fines,” says Chadwick. “It is more concerned about the application of mandatory buy-ins – and particularly the asymmetry of risk associated with the buy-in process.”

Eric de Gay de Nexon, head of strategy, market infrastructures and regulation at Societe Generale Securities Services (SGSS), points out that although CSDR entered into force in 2014, details of the SDR component were only detailed four years later, leaving the industry (including the ECB) with a broad set of open questions.

Eric de Gay de Nexon, head of strategy, market infrastructures and regulation at Societe Generale Securities Services (SGSS), points out that although CSDR entered into force in 2014, details of the SDR component were only detailed four years later, leaving the industry (including the ECB) with a broad set of open questions.

“Not all of these have been resolved, even today,” he says. “The market is far from being ready for this new settlement discipline regime.”

By granting additional time, this will allow participants to conduct end-to-end testing regarding the penalty regime and to address other issues. Previously, CSDR had been viewed largely as a ‘custodian topic’, whereas in reality this also has an impact at investment and trading level.

“Now a wider set of participants understand they need to be involved and are starting to ask broader questions,” says de Nexon. “For example, what will be the impact of the penalty on the NAV [net asset value]? And who should pay and receive the penalties, the asset owner or the asset manager?”

Matt Johnson, product management and industry relations specialist at DTCC, says news that European regulators have granted a short extension to the SDR deadline under CSDR will be welcomed by market participants. But it grants no time to relax.

“This delay is technical and doesn’t change any of the new rules within the Settlement Discipline Regime. So, despite the short reprieve, it is critical that market participants continue to ready themselves for SDR implementation in February 2021.

The market assumed this delay would be happening and have cautiously built it into their plans.”

Aviva’s Chadwick says: “One cheer to Esma for postponing implementation of the mandatory buy-ins and its system of penalties for failed settlement.”

A sizeable percentage of settlement fails happen for avoidable reasons, like errors in market participants’ static data or in standardised settlement instructions. The implementation of the Securities Financing Transaction Regulation (SFTR) during 2020 – which requires counterparties to provide detailed reporting of their securities financing trades, including securities lending and repo, to a trade repository – provides a spur for market participants to improve data quality and to eliminate a percentage of these avoidable settlement failures.

However, the industry has raised concerns about the impact that the introduction of mandatory buy-ins will have on secondary market liquidity in securities markets. The impact, Chadwick suggests, may be particularly acute at the less liquid end of the credit spectrum – for example, in emerging market or high yield debt – where market makers may be reluctant to quote a price in an instrument if they have fears about being bought in.

Chain of transactions

Roy Zimmerhansl, practice lead at Pierpoint Financial Consulting, explains that the settlement risk in securities lending transactions lies principally in the ‘return leg’, for example if the borrower fails to deliver a recalled security. Particularly for securities lending transactions in relatively illiquid securities like corporate debt, it may be difficult for the borrower to access recalled securities from alternative sources – and this may be contributing to higher settlement failures in today’s market, given the low current cost of fail claims.

The potential impact of the mandatory buy-in regime is complicated by the fact that the settlement process often involves a complex network of interlinked transactions – where a settlement failure can lead to the failure of a whole chain of settlement instructions.

For Simon Nottage, European head of securities finance product management at State Street, it is this chain effect that securities lending counterparties are finding difficult to model – the difficulties in tracking the movement of penalties along this transaction chain and its implication for the lender and borrower.

Expanding on this, Pierpoint’s Zimmerhansl says: “Borrowers failing to return a loan security will face a buy-in under the new regulation. However, this may also trigger a series of settlement failures along an interlinked chain of settlements. The result may be multiple buy-ins, including potential for the original lender to face a buy-in – for example, if it needs to recall the security because it has sold it in the cash market.

“Over time, beneficial owners may curtail their lending activity to avoid the risk of being bought in, to minimise reputational risk, even though it might be able to claim costs from the failing borrower.”

Existing remedies?

Many securities markets have operated a system of settlement fines for exchange trades (applied by a central counterparty or CSD, for example) for years – and counterparties have had discretionary avenues available to them where they can buy in securities in case of settlement failure (including the non-return of a loan security). Some argue that these existing remedies are adequate and that mandatory buy-ins will hurt more than they cure.

The Joint Associations recommend that this element of the CSDR implementation should be postponed until a more detailed impact assessment on the effects of this provision has been completed.

“Most asset owners currently have a contractual right to initiate a buy-in against a failing counterparty and exercise this on a discretionary basis,” says Adrian Dale, director of regulatory policy and market practice at Isla. For example, many transactions conducted on exchange are subject to buy-in provisions at the central counterparty or CSD if a counterparty fails to deliver securities.

For Aviva’s Chadwick, it is not obvious why Esma believes that mandatory buy-ins are a solution. Contractual remedies already exist where counterparties can buy one another in on a discretionary basis as an option of last resort. A system of mandatory buy-ins may improve settlement efficiency, but at the cost of a significant negative impact on underlying liquidity.

Isla’s Dale argues that existing discretionary mechanisms are in many cases sufficient. “If the regulators’ intention is to make settlement functions work more efficiently, we believe that the settlement fines provision in CSDR already provides a weighty enough stick to achieve this objective.”

Isla also proposes that before any mandatory buy-in takes place, there should be a partial buy-in (for example, using the T2S ‘auto-partial facility’) to reduce the outstanding exposure and the quantity of securities that needs to be bought in.

But others question how well existing discretionary buy-in arrangements really work to mitigate failed settlement in securities financing transactions. For Zimmerhansl, discretionary buy-in mechanisms already exist. But the penalties in the current interest rate environment may not be enough to ensure that borrowers return loan securities when requested.

“It is too simplistic to suggest that discretionary mechanisms are already in place and these are working effectively,” he says. “In previous times, when interest rate levels were higher, the interest rate cost attached to the claims process was often sufficient to encourage borrowers to do everything possible to return loan securities on time. But as interest rates have fallen – particularly for smaller trade sizes – this has often provided insufficient penalty to deter settlement failures.”

For clarification, Zimmerhansl explains that the value of the average corporate bond trade is much smaller than the average government bond trade, so the number of trades failing in corporate bonds tends to be much higher than government bonds. This is also part of the reason why more stocks fail. “Few people claim on stocks because the average ticket size is so small,” he says.

For SGSS’s de Nexon, the mandatory buy-in is “a kind of nuclear weapon whose consequences might have been underestimated. This should have been considered only as a measure of last resort in case the levels of settlement efficiency remain below the European Commission’s expectations.” He believes that a detailed assessment of the impact of the new penalty regime and the mandatory buy-in regime should have been conducted before it came into force.

© 2020 funds europe