The ‘QIAIF’ fund structure is a major statement of Ireland’s intention to maintain and expand its regulated hedge fund business. But competition from the Cayman Islands is stiff, let alone Ireland’s nemesis, Luxembourg. By Stefanie Eschenbacher.

Ireland, with its huge ambition to be dominant as a hedge fund domicile, revamped its alternative fund structure last year and has launched 35 new funds under the “QIAIF” label.

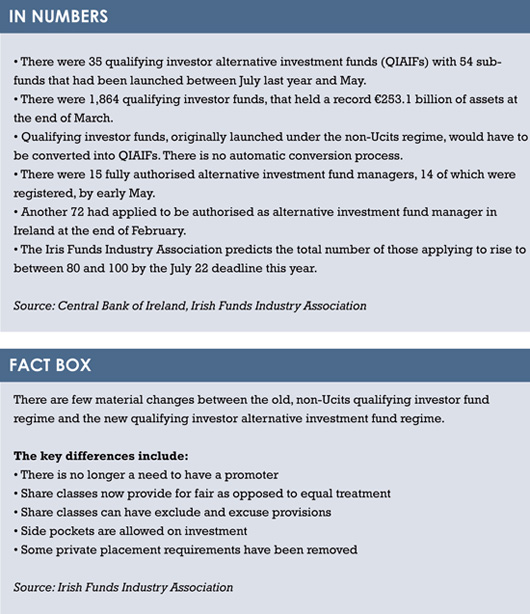

The QIAIF, or qualifying investor alternative investment fund, replaces the QIF, or qualifying investor fund. Even though there are few material changes, expectations are high.

Numbers from the Central Bank of Ireland show that the 35 QIAIFs launched since July last year have 54 sub-funds.

The whole QIAIF exercise takes place under the Alternative Investment Fund Managers Directive (AIFMD), transposed into national law in July 2013. The Irish Funds Industry Association, like its counterpart in Luxembourg, pitch the AIFMD as the next Ucits-style success: crossborder, transparent and, crucially, safe – only this time the “brand” covers alternative funds.

So far, there are 14 alternative investment fund managers that have been authorised by the central bank; another 72 applications have been filed. The central bank does not release data on applications that have been rejected or withdrawn.

Kieran Fox, director, business development, at the Irish Funds Industry Association (IFIA), says Ireland is still in a transitional period. Fox predicts that applications could rise to up to 100 by the July 22 deadline this year when applications will have to be filed.

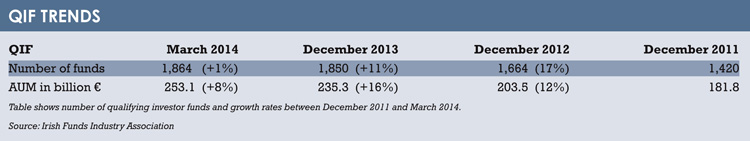

Ireland had to make few changes to its existing alternative fund regime, and Fox says the new structure should become as popular as its predecessor, the qualifying investor fund. The assets under management held in the 1,864 qualifying investor funds have reached an all-time high of €253.1 billion in March, even though growth has slowed.

“Pre-existing managers who had qualifying investment funds in Ireland would be already familiar with the requirements that apply at the fund level,” says Fox.

Among the 14 fund managers authorised by the central bank are so far few global heavyweights. BlackRock, the world’s largest asset manager, was the first one to receive approval from the central bank. On the first day of the new regime, the central bank authorised 150 of BlackRock’s alternative funds for sale in 15 different European countries under the AIFMD.

It was a promising start, and Ireland has loved to trumpet its readiness for the AIFMD world. The QIAIF is an unfolding story and so it remains to be seen whether this rival to Luxembourg’s specialised investment fund will live up to expectations in Ireland. But what is certain, is that Luxembourg and the Cayman Islands have as much intention as Ireland in dominating the hedge funds market.

OFFSHORE BATTLE

Cayman Islands-based Ian Gobin, who is partner and global head of funds at law firm Appleby, recalls that the initial expectation in Europe was that the AIFMD would become so popular that it would lead to the end of offshore jurisdictions. “The dust has now settled and it is becoming obvious that this is not going to be the case,” Gobin says, and he goes on to conclude that European fund managers have been returning to Cayman over the past year.

Gobin also says he is advising one European fund manager on re-domiciling its funds back to the Cayman Islands, having re-domiciled from the islands to Luxembourg only in 2008.

“It went well for a few years, but right now many European fund managers are saying that the cost of doing business in either Dublin or Luxembourg is prohibitive,” he says of his clients’ Luxembourg structures. “They are returning to the Cayman Islands.”

Service provider fees, legal fees and depositary fees are the main cost drivers in Europe. “The reason these fees are so high is because of the overly burdensome regulatory environment,” he says. “There is a regulatory paranoia in Europe, and this is played out in Luxembourg and Dublin.”

Gobin says that European regulators “want only the biggest managers to actually be in Europe” and emerging managers will neither be able to afford Europe nor be able to find a depositary. One option for fund managers is to set up one structure in Luxembourg or Ireland for their European investors, and a separate one in the Cayman Islands.

Both funds will pursue the same strategy, but Gobin says the returns for investors in the Cayman Islands structure will be greater because the costs are lower.

“Appetite in Cayman structures from European managers is increasing, in the rest of the world it never went away,” he claims.

But Shay Lydon, partner at law firm Matheson in Ireland, says the biggest selling point of regulated hedge fund structures in Europe is transparency, requirements for risk management and reporting.

“One of the things we have been talking about is the potential to have an alternative [fund] version of the Ucits brand,” he says, pointing to the success of Ucits that has even led some Asian countries to emulate the concept.

“Those investing in Ucits know that the process is quite straight forward, simply because they know that certain minimum standards have been met.”

But Gobin says institutional investors are highly sophisticated when it comes to due diligence.

“When they make an investment in a fund, are they relying on the regulation of the fund? Or are they relying on their own operational due diligence?”

Institutional investors appear to place little trust in the Securities and Exchanges Commission in the US – “nobody was relying on them to do a good job”, as Gobin puts it – and the failings during the financial crisis reinforced their attitude.

Gobin says investors do not rely on regulators when it comes to making sure the manager does what they claim they do.

However, in Ireland the reception of the QIAIF fund structure has nevertheless broadly been positive, says Lydon. When it comes to funds moving onshore or offshore, however, there is no clear trend.

WAIT AND SEE

Matheson recently published research it had commissioned from the Economist Intelligence Unit that shows 62.5% of managers are in a wait-and-see mode when it comes to the AIFMD. Meanwhile, at the IFIA, Fox says he is optimistic about the prospects of the QIAIF.

“Most managers are still using the full transitional period to become fully compliant with the new directive before they send in their application forms,” he says.

“Anecdotally, we are hearing from our member companies that there is strong interest to launch QIAIF in Ireland post the implementation of AIFMD.”

Donnacha O’Connor, partner at Dillon Eustace in Ireland, says fund managers and their sponsors are increasingly looking at regulated European funds that are not Ucits because of the AIFMD.

O’Connor says growth rates of QIAIFs are rivaling those of the specialised investment fund in Luxembourg, but says both have their target audience and there is a place for both.

While alternative structures in Luxembourg are typically used for real estate or private equity structures, Ireland’s QIAIFs are typically used for hedge fund structures. Ireland hosts more US and UK fund managers as a percentage of the total number of fund managers than Luxembourg.

While alternative structures in Luxembourg are typically used for real estate or private equity structures, Ireland’s QIAIFs are typically used for hedge fund structures. Ireland hosts more US and UK fund managers as a percentage of the total number of fund managers than Luxembourg.

Cayman Islands-based Ingrid Pierce, a global managing partner at law firm Walkers, says the European market is just too big to ignore and many of the larger managers are already complying with the AIFMD.

KEY SOURCE OF CAPITAL

However, she adds that the majority of non-EU investment managers have been quite slow to react to the directive and are only now beginning to face the reality of selling their products in Europe under the new regime.

“If the EU is a key source of capital for them, they need to assess their options pretty swiftly,” Pierce says, adding that they may need an AIFMD-compliant product – for example in Ireland – in order to attract European capital via the AIFMD passport.

She says that most funds in Ireland are established as self-managed investment companies, where the fund acts as both the alternative investment fund and the alternative investment fund manager.

Managers both within the EU and outside prefer this structure, Pierce says, because the obligations of AIFMD are placed on the fund and not the investment manager.

“This may account for the relatively low numbers of alternative asset managers authorised in Ireland and also seems to reflect the increase in the number of new funds,” Pierce of Walkers says.

Winning over managers outside the EU will be crucial to the success of the AIFMD; fund associations in both Ireland and Luxembourg have stepped up their lobbying.

There are 5,619 funds, including sub-funds, domiciled in Ireland that hold a combined €1.4 trillion of assets.

Fox says its investors come from more than 80 different countries and therefore “everywhere is a potential market” for the QIAIF.

©2014 funds europe