With such a large money market funds industry, Ireland is inevitably caught up in the regulatory push on shadow banking. Nick Fitzpatrick asks how Ireland and its service providers might be affected by money market reform.

Speculate that billions of euros, pounds or dollars will flow out from Ireland’s money market funds if proposed regulations are adopted in Europe and Pat Lardner, the chief executive at the Irish Funds Industry Association (IFIA), declines to “crystal-ball gaze”.

But he does question where any outflows might end up if restrictions on money market funds, proposed in Brussels last month, do shake the market this way.

“If you limit or restrict the use of these types of funds, where does the money go to? Does it go straight to the balance sheets of banks? This is where systemic risk comes from?”

NAV BUFFER

The irony is that the EU proposals for money market funds, which are part of a raft of measures to tackle risk in shadow banking, are partly aimed at containing systemic risk. A specific proposal – for a 3% buffer – is designed to help “constant net asset value” (CNAV) money market funds to withstand redemption pressure in stressed market conditions without resorting to their sponsors’ help.

The proposals look like being the EU’s most criticised set of proposed regulations since the first telling of the Alternative Investment Fund Managers Directive.

In the proposals CNAV funds – which seek to maintain a price of €1 a share, unlike “variable net asset value” (VNAV) funds – will have to use 3% of their assets as a NAV buffer.

For some people, this measure will inevitably lead to the conversion of CNAV funds into VNAV funds which, for Lardner – who acknowledges that most of Ireland’s many money market funds are CNAV – is pointless.

“Conversion to VNAV does not hit the point about systemic risk,” he says.

“Systemic risk does not occur because of a vehicle; it occurs because there are points in time when investors become nervous about markets, which transmits to a vehicle.

“We do not believe the VNAV is any better than the CNAV [for dealing with systemic risk].”

By maintaining €1 (or dollar, or pound) a share, CNAV funds are like bank accounts and maintain the net asset value so that outflows do not dilute returns for other investors. The buffer would be used to protect a CNAV fund from a sudden and large spate of withdrawals at a time of market panic, which can put pressure on the share price.

Money market funds invest in short-term debt securities. In Europe they hold around 22% of these types of securities issued by governments or by the corporate sector, and they hold 38% of short-term debt issued by the banking sector. It is this systemic interconnectedness with the banking sector and with corporate and government finance that has put money market funds in the shadow banking bracket.

But the 3% NAV buffer has implications for the economics of money market funds, affecting the ability to offer investors a decent yield. Low interest rates are a key challenge for the money market sector, across all currencies.

UNAVAILABLE CAPITAL

Cathal O’Daly, head of client and sales management for financial institutions at Citi, says yields are already compressed by low interest rates on short-term securities. “The proposed buffer will add further yield compression as the capital is tied up and unavailable for use.”

Tara Doyle, a partner at Matheson law firm in Dublin, explains why she thinks the NAV buffer is “potentially very damaging” for the industry.

“As a result of the ongoing ultra-low interest rate environment, many MMF [money market fund] managers are already waiving advisory fees and reimbursing fund expenses, or earning net fees measured in single basis points. The imposition of a 3% capital buffer would in effect mean that many MMFs could no longer exist.”

“As a result of the ongoing ultra-low interest rate environment, many MMF [money market fund] managers are already waiving advisory fees and reimbursing fund expenses, or earning net fees measured in single basis points. The imposition of a 3% capital buffer would in effect mean that many MMFs could no longer exist.”

The buffer will limit the kind of yield that a CNAV fund can offer to investors, and yield may be one of the main reasons why investors choose them.

The Institutional Money Markets Fund Association, which is based in London and represents CNAV funds, says holding a capital buffer is inappropriate for money market funds and it also expects the proposals to acts as a trigger for the conversion of CNAVS to VNAVs.

Lardner says conversions would reduce choice for investors, some who are large and sophisticated and choose CNAV products to address risk and liquidity needs.

But he says that Ireland, due to its service providers, has the capability to service VNAV funds as much as it does CNAV.

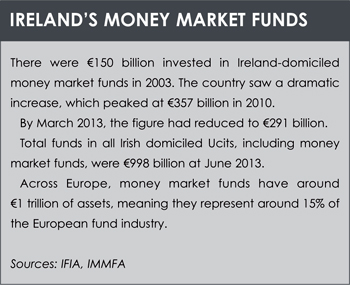

Ireland had €274 billion of money market funds domiciled there at the end of June (see box).

BlackRock is one of the largest providers. Its BlackRock ICS – Institutional USD Liquidity Fund held $22.5 billion (€16.6 billion), at August 16. Its euro fund, the largest in Europe in the currency, held €12.4 billion, and its sterling fund, also the largest in Europe, held £24.6 billion (€29.3 billion).

Asked about the implications for Ireland’s service providers, O’Daly, says: “Clearly at this early stage, the practicalities of applying the buffer have to be considered and tested in a little more detail. Additional rules will have to be built into systems, which of course can be done. Fund administration systems are more than capable of including automated rules that can check for buffer’s and facilitate any additional controls and checks.”

COSTS

He adds that fund conversions will result in costs. “The introduction of the buffer will most likely result in conversion of CNAV to VNAV funds, resulting in one-off additional costs to providers and promoters.

“Most VNAV funds will continue to operate like CNAV funds whilst maintaining the ability to ‘break the buck’ [go below €1 a share]. They will implement new capabilities to liquidate or destroy units or create side pockets to warehouse default assets should a default event arise,” says O’Daly.

“These processes will result in incremental cost to providers to monitor and support.”

Further downstream, there may also be implications for service providers in Ireland and elsewhere.

“This creates pricing pressures and on all service providers to the fund. At some point, the economics may not just add up for the service providers, which in itself, could impact the industry,” says O’Daly.

The Financial Stability Board estimated in 2011 that shadow banking was worth around €51 trillion globally. Europe’s money market funds are €1 trillion of that.

For Lardner and the IFIA, an overarching issue is the failure of the EU to act in tandem with overseas authorities over money market funds. Notably the US does not require a NAV buffer for CNAV funds.

©2013 funds europe