Back to the topic of fund governance – this time with a focus on fund services and compliance. In the cross-border European world of UCITS funds, third-party management companies (known as outsourced ManCos) play a crucial role in regulatory compliance and governance. In the UK, Authorised Corporate Directors (ACDs) – which can also be ‘hosted’ (outsourced) – have full regulatory and governance obligations for day-to-day fund operations.

Scrutiny of ACDs has become intense since the turmoil surrounding fund manager Neil Woodford. The FCA is now investigating them.

Shiv Taneja, founder and chief executive of the Fund Boards Council, which promotes good governance on fund boards, said the Woodford debacle had thrown open serious issues around the governance of funds.

Taneja believes there was “a complete breakdown of multiple sets of actors”, with failures at four levels: the regulator (the FCA), the external outsourced governance team, otherwise known as the ACD (Link Fund Solutions), a distributor (the online broker Hargreaves Lansdown, which recommended the fund to its clients who, in turn, held 31% of the gated Woodford fund at the end of 2018) and Woodford Investment Management itself.

“I think each one of them has got to take responsibility for certain things that they ought to have done and didn’t do that could have mitigated risks,” says Taneja.

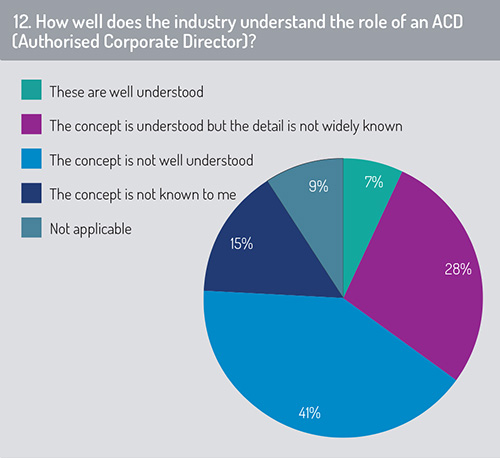

We asked the question: How well does the industry understand the role of the ACD (fig 12)?

Forty-one per cent said the concept was not well understood and 28% said the concept was understood but the detail was not widely known.

Forty-one per cent said the concept was not well understood and 28% said the concept was understood but the detail was not widely known.

The ACD is a UK concept. Given that 12% of our respondents were from the UK, the higher level of non-UK respondents could have influenced the less-than-favourable result.

Just over 20% of respondents were from Luxembourg, where the ManCo – which is broadly comparable in nature to the UK’s ACD – is firmly established.

Asset managers are keen outsourcers of their middle offices, which is largely the operational area of regulation and compliance. Third-party ManCos are specifically set up to capture this area of outsourcing.

Asset management firms are – or should be – aware that whereas they can outsource the function, they cannot outsource the responsibility.

However, outsourcing this area has become rampant. There has been a highly accelerated growth of the ManCo market. In Luxembourg alone, there were 429 ManCos employing a total of 5,700 people at the end of 2018, according to PwC’s ‘Observatory for Management Companies’ 2019 report.

Furthermore, figures from the Association of the Luxembourg Fund Industry published in March 2019 showed that half of these firms had less than €1 billion of assets under management, which represented just 12% of the total assets in Luxembourg’s ManCo market. Just six ManCos in Luxembourg had more than €25 billion in assets under management.

Furthermore, figures from the Association of the Luxembourg Fund Industry published in March 2019 showed that half of these firms had less than €1 billion of assets under management, which represented just 12% of the total assets in Luxembourg’s ManCo market. Just six ManCos in Luxembourg had more than €25 billion in assets under management.

Meanwhile, the Central Bank of Ireland has received more than 100 applications from UK-based firms wanting to set up ManCos to ensure Brexit does not affect their ability to operate cross-border funds.

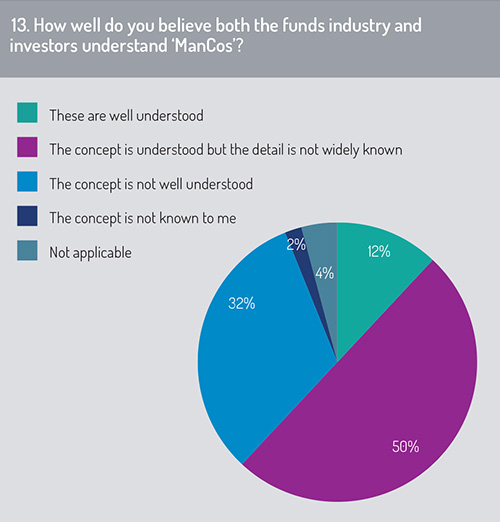

So, how well understood is the ManCo? We asked this question (fig 13) and perhaps the most significant score was the 50% who said the ManCo concept was understood but the detail not widely known.

We further found that 32% of respondents who answered the question said the ManCo concept was not well understood. However, 12% did consider the idea of the ManCo to be well understood.

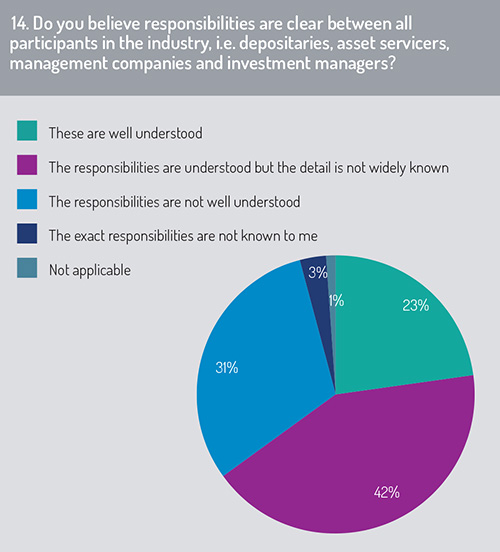

Digesting these results, it may be reasonable to ask if there is a significant lack of knowledge about the role in governance that the ACD and ManCo entities have – and given the lack of clarity that some respondents believe exists, whether this affects the quality of fund governance, particularly as outsourcing has proliferated. The question is acute for hosted ACDs, given that Woodford – and more pertinently his investors – relied on one.

Digesting these results, it may be reasonable to ask if there is a significant lack of knowledge about the role in governance that the ACD and ManCo entities have – and given the lack of clarity that some respondents believe exists, whether this affects the quality of fund governance, particularly as outsourcing has proliferated. The question is acute for hosted ACDs, given that Woodford – and more pertinently his investors – relied on one.

“The Woodford situation is an extreme example of how desperately wrong things can go when there is either an absence of governance or when organisations don’t do what they are supposed to do,” Taneja says.

Partly triggered by Brexit, but very much with the emphasis on investor protection, regulators in the main cross-border fund domiciles of Luxembourg and Ireland have brought more scrutiny on ManCos. Questions are being asked of their balance sheets, operating models and human resources, in other words that they have genuine substance in terms of staff and expertise.

At the height of Brexit uncertainty two years ago, a number of asset managers, such as M&G Investments, set up their own ManCos, mainly because they were uncomfortable with the lack of choice in the third-party market. Keeping this area of fund governance in-house may be seen as a tougher form of fund governance for an asset manager to take. However, increased standards for expertise set by the regulators, coupled with the fact that ManCos have an extra two years of track record since regulatory scrutiny began, suggest the evolved outsourced ManCo model is set to thrive.

At the height of Brexit uncertainty two years ago, a number of asset managers, such as M&G Investments, set up their own ManCos, mainly because they were uncomfortable with the lack of choice in the third-party market. Keeping this area of fund governance in-house may be seen as a tougher form of fund governance for an asset manager to take. However, increased standards for expertise set by the regulators, coupled with the fact that ManCos have an extra two years of track record since regulatory scrutiny began, suggest the evolved outsourced ManCo model is set to thrive.

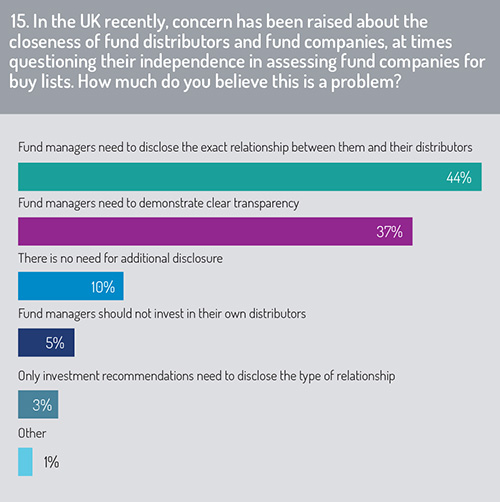

The role of the distributor (namely Hargreaves Lansdown) in the Woodford blow-up has also caused a good deal of scrutiny, so we asked our respondents if they felt the closeness of fund distributors and fund manufacturers was a problem (fig 15).

Again, this was a multiple-choice question and the answer with the highest rating (44%) showed respondents felt fund management companies needed to disclose the exact relationship between them and their distributors. Some 37% said fund managers needed to demonstrate clear transparency. A paltry 10% were comfortable with the current level of disclosure.

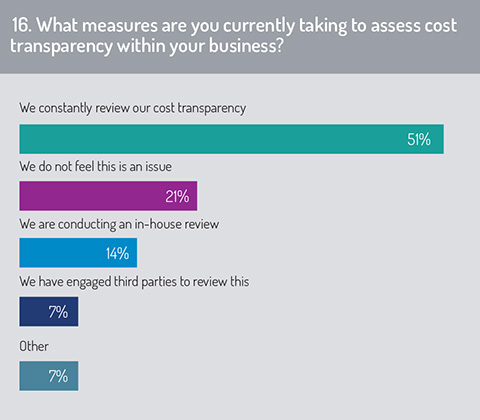

A related question here, although not necessarily relevant to all respondents (150 of the 177 in total answered it), was: What measures are you currently taking to assess cost transparency within your business (fig 16)?

A related question here, although not necessarily relevant to all respondents (150 of the 177 in total answered it), was: What measures are you currently taking to assess cost transparency within your business (fig 16)?

Just over half said cost transparency was constantly reviewed; 21% said they did not feel it to be an issue; and a total of 21% said they were conducting a review in-house or had engaged a third party.

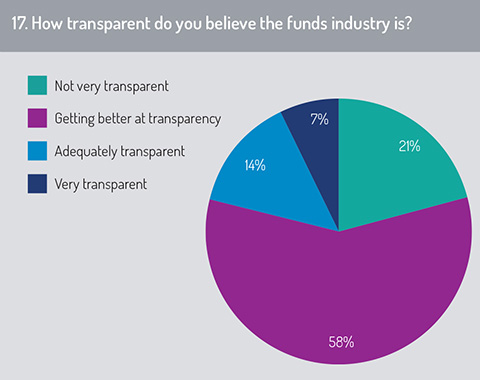

On the whole, it appears that fund professionals do not consider the industry to be adequately transparent (fig 17). Nearly 60% said the industry was getting better at transparency but 21% described the industry as “not very transparent”. Twenty-one per cent said transparency was adequate or very good.

All the above topics, and others covered by our survey, are being steered by regulators. ESG, for example, is barely an option any longer. Investors are under increasing policy pressure to enact ESG investing and to take action over climate change.

All the above topics, and others covered by our survey, are being steered by regulators. ESG, for example, is barely an option any longer. Investors are under increasing policy pressure to enact ESG investing and to take action over climate change.

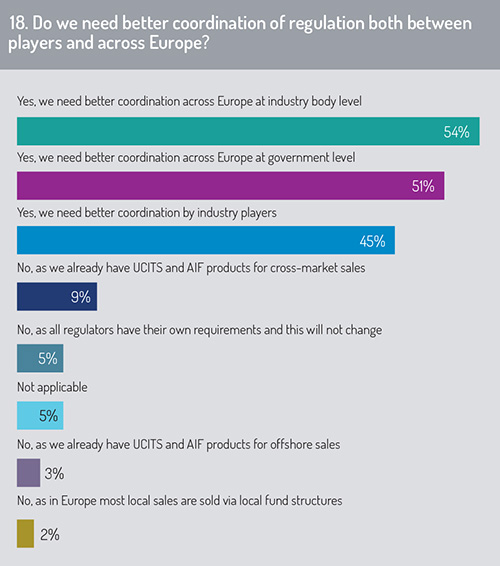

As regulators have increasingly implemented and devised new rules for the funds industry over the past decade and continue a granular level of scrutiny, fund professionals in our survey voice a well-known frustration within the sector: a lack of ‘joined-upness’. They want to see better coordination across Europe (fig 18), primarily at the industry-body level (54%), then at the government level (51%), and also between various industry players themselves (45%).

Until this happens, then without everyone ‘on the same page’, there will inevitably be different standards of governance across the EU, including its departing member, the UK.

© 2020 funds europe