David Whitehouse reports on how endowments are venturing into cryptocurrencies as they seek to match Yale’s track record.

Endowment funds aiming to repeat the kind of long-term returns achieved by David Swensen at Yale University’s endowment fund are considering new asset classes such as cryptocurrencies as private market opportunities dwindle.

The annual average return during Swensen’s 35 years as chief investment officer at Yale was 13.1%. He embraced illiquid markets such as private debt and equity that few had dared to explore.

The endowment, worth $1.3 billion when Swensen took over in 1985, is now worth $42.3 billion and covers about a third of the university’s annual budget. That rises to 58% if the medical school, which gets grants and clinical income funding, is excluded.

Swensen, who died last May, showed that there were “more colours to paint the portrait with”, says Ahmed Husain, head of family offices and endowments at Neuberger Berman in London. “Initially he was ridiculed.” Cryptocurrencies and frontier emerging markets are the new asset classes where an open mind is needed now, Husain says. Around 5% of endowment offices now have some exposure to cryptocurrencies such as bitcoin and ethereum, he says, with some endowments seeing crypto exposure as a way to hedge their exposure to gold.

He points to the fact that only 21 million bitcoins will ever exist as underpinning the scarcity value that supports gold’s appeal. The mistrust of official currencies which also supports gold makes cryptocurrencies a logical complement for such investors, he adds.

Neuberger Berman manages money for high-end endowments, typically with assets above $1 billion, and sources other fund managers where appropriate. There has been a trend for endowments to invest in illiquid markets such as private debt, private equity and venture capital, and this is likely to continue, Husain says. There is “more alpha in private markets”.

Small is beautiful

The Yale endowment fund’s report for 2020 says that the framework for investment decisions rests on mean-variance analysis, as developed by Nobel laureates James Tobin and Harry Markowitz. Statistical techniques are used to combine expected returns, variances and covariances of assets. Qualitative considerations also play an important part. Quantitative measures, the report says, have difficulty incorporating factors such as market liquidity or the impact of low-probability events.

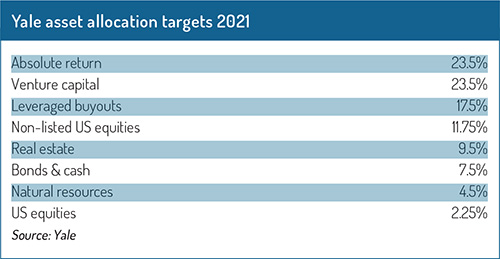

The fund defines eight asset classes in terms of the differences in their expected response to economic growth, inflation or interest rate changes. It targets a minimum allocation of 30% to market-insensitive assets and seeks to limit illiquid assets, such as venture capital, leveraged buyouts, real estate and natural resources, to 50% of the portfolio. The university’s vulnerability to inflation means that fixed income gets a low weighting. More than 90% of the fund is intended to be invested in assets that produce “equity-like” returns.

The asset allocation targets for 2021 were 23.5% each for absolute return and venture capital, 17.5% in leveraged buyouts, 11.75% in non-US equities, 9.5% in real estate, 7.5% in bonds and cash, 4.5% in natural resources and just 2.25% in US equities.

Even in US stocks, Yale pursues an active strategy, believing that outperformance is possible.

The university targets an annual spending rate of 5.25% from the fund, but rules exist to smooth out the impact of volatile returns. Distributions from the fund don’t immediately fall in line with periods of underperformance, and neither do they rise fast when performance improves.

Yale was an early mover that stood out from the crowd because its asset allocation, especially in private markets, differed from its peers, says Paul Cummings, head of family offices, foundations and endowments at Fiduciary Trust International in New York. Private markets, he notes, are larger and deeper today. Though the scope for returns on the scale achieved by Yale has been reduced, there is still opportunity for outperformance, he says. “I don’t believe those days are gone. There will remain good opportunities in private markets.”

Yale was an early mover that stood out from the crowd because its asset allocation, especially in private markets, differed from its peers, says Paul Cummings, head of family offices, foundations and endowments at Fiduciary Trust International in New York. Private markets, he notes, are larger and deeper today. Though the scope for returns on the scale achieved by Yale has been reduced, there is still opportunity for outperformance, he says. “I don’t believe those days are gone. There will remain good opportunities in private markets.”

Cummings sees potential in the way different assets are combined in portfolio construction to deliver outperformance. Overall risk, he says, can be reduced, for example, by combining private debt with a diversified basket of commodities.

The prestige of funds such as Yale, Harvard and Stanford gives them an advantage in finding the best opportunities, says Bill Thompson, director of endowments and foundations at Litman Gregory in San Francisco. He still sees room for smaller, unknown endowments to earn a premium to public markets. The illiquidity premium, though reduced over the past five years, still exists, he says.

There is clearly more capital now going into alternative assets, which will have a “muting effect” on future returns, Thompson says. Some underexplored niche markets are too small for the biggest endowments to be able to make a meaningful allocation, and that will favour the smaller players, he argues. The long-term time horizon of endowments will work in their favour, he adds. “The bottom line is that endowments have time on their side.”

© 2021 funds europe