Concerns are growing that Luxembourg’s negative rating for tax transparency standards will scare off supranationals and large institutional investors. Stefanie Eschenbacher finds the move is perceived as a politically motivated one.

It was another slap in the face for Luxembourg when the Organisation of Economic Co-operation and Development found it to be non-compliant with tax transparency standards at the end of last year. Luxembourg was temporarily on the grey list of countries seen as lacking financial transparency once before, in 2009.

Along with Ireland and the Netherlands, it is also under investigation by the European Commission and has to prove that it is not acting as a tax haven by allowing tax avoidance structures of multinationals.

Concerns are growing in image-conscious Luxembourg that the negative rating – which lumps the country together with the British Virgin Islands, Cyprus and the Seychelles – will have an impact on the way business is done.

It was awarded through a working group of countries that have agreed to implement transparency and exchange of information for tax purposes: the Global Forum on Transparency and Exchange of Information for Tax Purposes.

The assessment refers to the years between 2009 and 2001, and those in Luxembourg are quick to point out that things have changed since then. The move is perceived as unjust and politically motivated.

“Everybody fights with everybody and everybody competes for market share,” says Freddy Brausch, managing partner, global co-head of the investment managers sector, at Linklaters.

He says rivals will try to “temporarily harm or make life more difficult” if they believe this will result in more market share.

POLITICAL DIMENSIONS

Nicolas Mackel, chief executive of Luxembourg for Finance, says the negative rating “does not reflect the reality” and that there are “political dimensions” to it. “This is part of an attempt to discourage investors to use Luxembourg and it is part of a global competition war, which is waging, and which has certainly increased since the financial crisis.”

Mackel, who describes the development as a “major image problem”, says this criticism is taken seriously and regulation will change in order to be compliant.

“We do not want to be seen as non-compliant,” he says. “It is extremely important to us, from a reputational point of view, to remain an attractive destination for investors.”

Patrick Mischo, partner at Allen & Overy, says Hong Kong, Singapore and other offshore centres face similar pressures when it comes to transparency.

“What happened was an opportunity because Luxembourg was pretty reluctant to give up on banking secrecy,” Mischo says.

“And at some point people understood that it probably would have to go with the trend because it is much more important to have an excellent reputation as a financial centre than trying to do the business it used to do before.”

While Mackel says it is not clear what impact the negative rating will have, Brausch says supranationals and other institutional investors will indeed pay attention.

Sovereign wealth funds, large pension funds – certainly government-backed funds – and endowments will be under the influence of their respective governments.

“We cannot afford to say we do not care,” Brausch says, adding that Luxembourg has been in contact with supranationals, the European Central Bank and the European Investment Bank.

“It is difficult to assess the impact, but it is something which supranationals and institutions will be looking at when setting up stuctures or when investing,” Brausch says.

His colleague, Olivier Van Ermengem, also a partner, says that the reasons for the negative rating were questionable in the first place.

Luxembourg, for example, did not act when other countries requested data of taxpayers whose details were obtained from a stolen CD. It also informed taxpayers when a request for information about them was submitted. Some of the requests dated back to before the agreements were signed.

Mackel says some of these requests, such as acting upon information that had been stolen and not informing taxpayers when a request for information about them was submitted, are contrary to Luxembourg’s understanding of a rule of law.

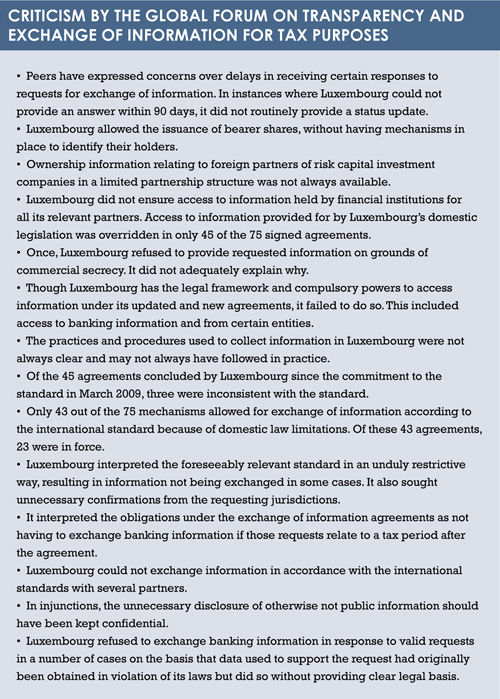

Its peers, however, were not always convinced (see box).

“Luxembourg feels frustrated and ill-treated,” says Van Ermengem. “It comes at a bad and ill-chosen moment.”

Luxembourg has transposed an EU directive for the automatic cooperation in taxation into its tax law and will offer automatic exchange of information as of 2015.

In an official response, the Luxembourg government says the negative rating is “inappropriately severe” because it is already committed to effective exchange of information and had replied to hundreds of requests.

During the period under review, the country received 832 requests and replied to 785.

Luxembourg argues that only a “highly limited” number of its replies were considered unsatisfactory.

Luxembourg argues that only a “highly limited” number of its replies were considered unsatisfactory.

Others in Luxembourg are quick to dispute the overall outcome, too.

Mischo says the press coverage has led to a discussion. “It is not only about image, it is also the fact that there is something in the press that results in your clients raising questions.”

Mischo adds that this could also lead to a situation where asset managers are facing questions from their investors, and that some operators have already expressed concerns.

“The discussion is about jealousy,” he says. “This is a political exercise… and the feeling here in Luxembourg is that there is some Luxembourg-bashing.”

Mackel says Luxembourg is also seen as “blocking” the discussions on the extension of the scope of the savings directive by the EU.

Although Luxembourg says it shares the objective of the directive, it has raised concerns to extend the scope to revenues other than interest.

“These European discussions … were a fantastic stick to help beat Luxembourg,” he says, adding that there is already a lot of pressure on Luxembourg.

Still, Mackel says he does not expect the country’s assets under management – institutional, sovereign or private – to go down dramatically.

“What investors value Luxembourg for is solidity: Luxembourg is one of the few countries with a AAA rating, a stable political environment, a stable fiscal environment.”

Thibaut Partsch, a partner at Loyens & Loeff, shares this line. Partsch says that Luxembourg focuses on fairness and tax questions, but at the same time makes sure that its fund industry prospers.

“I have never done bearer shares,” he says of another point of criticism. “My clients like confidentiality, but for legitimate reasons.”

Partsch says just because someone is looking for privacy, it does not mean they hide something from the authorities.

“We are not in a situation where the phone has stopped ringing,” he adds.

Mischo points out that Luxembourg is also in negotiations with the US regarding the Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act and is pro-exchange of information but would like there to be a global level playing field.

The Ministry of Finance in Luxembourg has not responded to requests for an interview.

©2014 funds europe