Fund managers want to be seen as socially useful. Alternative lending – made so necessary by lower levels of finance from traditional sources – could be the ticket, as long as the right vehicles are found, reports Fiona Rintoul.

“The quiet revolution” is how Jack Inglis, chief executive of the Alternative Investment Management Association (Aima), describes the change taking place in the way companies secure their finance.

As banks have scaled back their lending activities in the face of regulatory pressure, fund managers are stepping into the breach, urged on both by the ongoing search for yield and by the European Commission’s Action Plan for Capital Markets Union (CMU), introduced in 2015, which has an increase in non-bank lending among its aims.

Although some industry observers have questioned whether fund managers have the right expertise and long-term approach to lend, a greater role for fund managers in company finance has been broadly welcomed by the industry.

“It’s helpful for everyone,” says Patrik Karlsson, director of market practice and regulatory policy at the International Capital Market Association (ICMA). “Investors get access to diversified sources of income and companies get more options for funding. Furthermore, investors often have long-term liabilities well suited to this activity.”

In any case, lending by fund managers is nothing new. Denise Voss, chairman of the Luxembourg funds industry association (Alfi) notes that debt funds, including debt origination and direct lending funds, have been offered out of Luxembourg for 20 years.

Bob Parker, senior adviser in the investment, strategy and research group at Credit Suisse, adds: “Since the 2008 financial crisis, there has been a clear deleveraging of risk assets on bank balance sheets, while asset managers, in response to historically low bond yields, have diversified into a range of asset classes previously managed on bank balance sheets.”

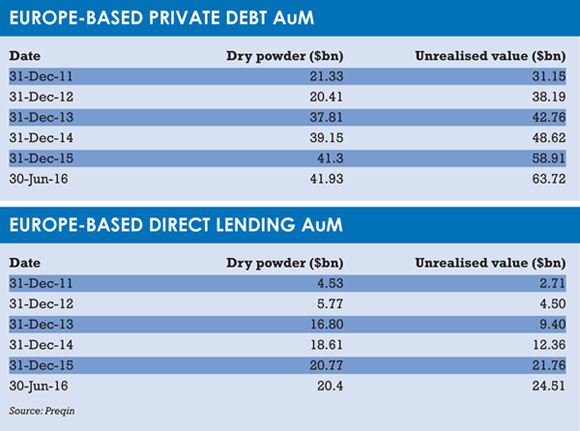

According to data provider Preqin, the private debt industry in Europe has seen five consecutive years of growth in fundraising since 2010, though its upwards trajectory appears to have halted in 2016. The total capital raised by Europe-focused funds at the time of Preqin’s ‘November Private Debt Spotlight’ was $17 billion (€16.3 billion), compared to $33 billion the previous year.

Nonetheless, at $41.9 billion (so-called dry powder – see tables, page 10), assets under management in Europe-based private debt funds are almost twice what they were in 2011 and had quadrupled in direct lending funds.

TRADITIONAL MANAGERS

Such is the magnitude of the increased role such alternative fund managers are set to play in financing the economy in Europe that Aima has even set up a new trade association, the Alternative Credit Council. As well as firms with private equity backgrounds, some traditional long-only managers have also become important in the sector and more are likely to.

“Nearly every fixed income specialist is now expanding, launching or exploring new private lending products,” says Chris McChesney, senior vice president, investor services, at Brown Brothers Harriman.

In Europe, the introduction in 2015 of the European long-term investment fund (Eltif), a regulated vehicle that can invest in various asset classes, may bolster the trend for traditional fund managers to become involved in alternative lending.

So far only a small number of Eltifs has been launched, including two in France and two in Luxembourg, but some observers see huge potential.

“It looks to me like everyone is waiting for the first ones to start,” says Silke Bernard, a partner at law firm Linklaters in Luxembourg, which has seen interest from some of the “biggest asset managers in the world”.

As is clear from the list of eligible asset classes for Eltif, the scope for alternative lending is wide, from small enterprises to climate change finance.

In October 2016, the Luxembourg government and the European Investment Bank (EIB) launched the Luxembourg-EIB Climate Finance Platform, which aims to mobilise investments for projects with a strong impact in the fight against climate change. This is not just a potentially interesting new asset class; it’s also an opportunity for the fund industry to make a useful social contribution.

“It’s a big opportunity,” says Voss. “It fits into our responsible investment pillar and is another means for the fund industry to help. For me, it’s an infrastructure element as well.”

TRADITIONAL VEHICLES ARE USEFUL

However socially useful these investments may be, the new vehicles created to facilitate them have not found favour with everyone. Irish loan origination funds, for example, have not been as popular as expected, and the Irish authorities have had to revisit the product to add more flexibility, notes Jiri Krol, deputy chief executive of Aima.

“Some of the vehicles created have not been that helpful, because they are quite restrictive in terms of eligible underlying assets and use of derivatives,” says Krol. “Generally, we don’t need regulated vehicles. People are using traditional vehicles used for hedge or private equity strategies.”

The fact that the vehicles are not regulated should not cause concern, says Krol, as the managers are regulated through the Alternative Investment Fund Managers Directive (AIFMD).

The fact that the vehicles are not regulated should not cause concern, says Krol, as the managers are regulated through the Alternative Investment Fund Managers Directive (AIFMD).

“Adding extra product-specific rules is not necessary or desirable at the moment,” he says.

That’s fine if you agree with him that this is “an institutional story at the moment”. Eligible investors for unregulated vehicles – such as Luxembourg’s reserved alternative investment fund (Raif) introduced at the end of 2015 – are institutional investors, professional investors and other investors with at least €125,000 to invest.

The Eltif, by contrast, is designed for both institutional investors and better-off retail investors with €10,000 or more to invest. Alfi certainly hopes some mass affluent investors will come on board.

“I would hope it would fire the imagination of retail investors too, but there is obviously an investor protection element and an investors knowledge element,” says Voss.

For retail investors, certain protections are in place with Eltif. Voss believes it falls to fund managers to help plug the investor knowledge gap. In some ways, digitalisation may make this easier, as it brings fund management companies into direct contact with investors, even if only online.

“If we do really want to make this attractive, we need to explain what it’s about,” Voss says. “It’s not easy, but we should do it.”

However, as the sector develops, the need for investor protection in Eltifs may rub up against alternative lenders’ desire for as much freedom as possible. One observer favoured more flexibility in Eltifs such as limits on leverage being relaxed.

Meanwhile, any notion that fund managers will not be as good at assessing the credit-worthiness of borrowers as the banks are is disputed by many in the industry. After all, banks did not exactly cover themselves in glory in this area during the 2008 financial crisis.

“Fund managers that undertake this activity have dedicated credit desks,” says Karlsson. “As long as the activity is soundly regulated and fund managers undertake appropriate due diligence, the risks are manageable.”

It may be, however, that more information needs to be made available to alternative lenders to allow the market to function as well as possible. Voss draws a comparison with the US market. “If you look at the US credit rating agencies and the information available to banks and other lenders, we have a long way to go in Europe,” she says.

In the meantime, much may depend on the success or otherwise of Eltif. The key advantage of that structure is not just that it has the ability to passport across Europe, but that the funds can lend cross-border.

“That’s why you see Esma [European Securities and Markets Authority] putting out an opinion about loan origination funds,” says Krol. “The litmus test will be the success at the local level of funds such as Eltif.”

In some ways, however, these are details – albeit important ones. A fundamental change is taking place in how companies and other projects are financed in Europe and by whom. Alternative lending is just part of a bigger picture that encompasses crowdfunding, peer-to-peer lending and a revival of securitisation. It’s a change that puts fund managers right at the heart not just of the finance sector, but of society.

“More private lending by asset managers is a significant structural change in capital markets and it’s here to stay,” says McChesney. “This toothpaste is not going back in the tube.”

©2016 funds europe